Lysenko,

Hunka and the Ukrainian Art Song

By Wasyl Sydorenko

One of the reasons why I am

writing this review in English is because the term art song has no

Ukrainian-language equivalent. This may come as a surprise since Ukrainian

composers have been writing art songs for nearly 150 years. And yet, there is

no Ukrainian word or phrase that describes this genre – one of the highest

forms of vocal art in European music.

In the Austro-German

tradition, the art song is known as the Lied, and in French as a mlodie.

In Ukrainian, the following terms have been used – , , , or

– with the last one coming closest to the semantic meaning of the term,

but without capturing its essence. Basically, an art song is a classical

composition that combines voice(s) and piano as partners in a musical setting

of poetry. The voice is not unlike an instrument and the accompaniment is not

unlike a soloist. Both combine to create a total musical experience.

During the 19th century,

For the next 25 years,

Lysenko continued, almost exclusively, to set the poetry of Shevchenko to

music. During this time, he attempted to create a Ukrainian version of the art

song based on compositional techniques and melodic elements derived from

Ukrainian folk songs and dumy. How successful he was is still a matter

of debate among musicologists and music-lovers.

In 1893, with the

composition of his song cycle to texts by Heinrich Heine, Lysenko all but

turned his back on Shevchenko and began setting to music the poetry of

contemporary Ukrainian writers – I. Franko, L. Ukrainka, O. Oles, etc.

Musically, too, there was a noticeable shift away from the folk song as Lysenko

began to imitate German composers and explore more modern styles of

composition.

There is a lot about Mykola

Lysenko that we do not understand. As a composer, he has been mythologized to a

point where we can no longer see him as he truly was. But, he was not the

father of classical music in

Nevertheless, Lysenko

composed more than 120 art songs and influenced almost every other Ukrainian

composer that followed him. This, indeed, is one of his most important

legacies. And yet, for more than a century, Lysenko’s art songs remained either

unpublished or unperformed. The publication of his collected works in the 1950s

failed to encourage musicians to explore this legacy. If concert programs were

strictly controlled by censors in Soviet Ukraine, why weren’t Lysenko’s art

songs performed by singers in the Diaspora?

Without a performance

tradition or practice, it is not surprising that Lysenko’s oeuvre of art

songs baffled many a singer, including opera baritone Pavlo Hunka when he first

discovered them. Indeed, these were not arrangements of folk songs or salon

romances; these were concert hall art songs. Pavlo promised his father that one

day he would perform them and that the whole world would hear the beauty of the

Ukrainian art song.

Without a performance

tradition or practice, it is not surprising that Lysenko’s oeuvre of art

songs baffled many a singer, including opera baritone Pavlo Hunka when he first

discovered them. Indeed, these were not arrangements of folk songs or salon

romances; these were concert hall art songs. Pavlo promised his father that one

day he would perform them and that the whole world would hear the beauty of the

Ukrainian art song.

And so, Pavlo Hunka, the

Artistic Director of the Ukrainian Art Song Project (UASP), has devoted

his life to rediscover and promote world-wide the art songs of Ukrainian

composers, and to demonstrate that they are indeed part of the European

tradition of classical vocal music. The project has generated the term , which has been used by

After more than a decade of

intense preparation and collaboration with other performers, musicologists,

researchers, literary specialists, volunteers and sponsors, the art songs of

Mykola Lysenko were finally launched at a concert in Koerner Hall at the Royal

Conservatory of Music in

The concert première

of Lysenko’s art songs should go down in history as one of the greatest

achievements in Ukrainian classical music. Pavlo Hunka was assisted by fellow

singers Monica Whicher, Krisztina Szab, Russell Braun, pianist Albert Krywolt,

cellist Roman Borys and flautist Julie Ranti. These are but a few of the names

that appear on the recordings, which include: Isabel Bayrakdarian, Allyson

McHardy, Elizabeth Turnbull, Benjamin Butterfield, Michael Colvin, Robert

Gleadow, Mia Bach, Serouj Kradjian, and Douglas Stewart.

Canadian broadcaster Stuart

Hamilton was the host, Melanie Turgeon introduced the project’s online music

library (www.uasp.ca), the Chair of the Executive Committee Lesia Babiak

thanked all those who contributed to the project, and chief fundraiser William

Zyla thanked all the donors and sponsors. The list of names is long and

impressive. A special tribute was offered in honour of the late Richard

Bradshaw, Artistic Director of the Canadian Opera Company, for his support of

the project.

Not enough can be said

about the actual performance of Lysenko’s art songs. To create a performance

practice where none existed, especially one conforming to European tradition,

was no mean feat. This proves that Lysenko’s art songs do belong to the

classical tradition of European music. The interpretation of each art song was

remarkably insightful. The Ukrainian diction was nearly impeccable. The

renditions were pleasing to both the native and non-Ukrainian listener, and

musically convincing to any fan of vocal art. Truly, a job well done!

Roman Hurko returned as the

producer of the UASP’s Lysenko album. The recordings have a bright and

intimate sound, perfect for the genre. They are accompanied by a 207-page book

with annotations by Dagmara Turchyn and Wasyl Sydorenko. The 124 tracks of

songs are organized by theme into 6 CDs: Nature, Love, Fate,

A Historical Theme, A Philosophical Theme, and The Song Cycle

“A Poet’s Love”. The album is a milestone of performance practice and the

beginning of a new chapter in Ukrainian musicology. For the first time,

classical music lovers, students of Ukrainian music history, and performers

around the world can appreciate the creative genius of Mykola Lysenko. Thank

you, Pavlo, for your vision and your determination to see this stage of the UASP

through to completion. Bravo and encore!

Wasyl Sydorenko is a

musicologist and composer in Toronto,

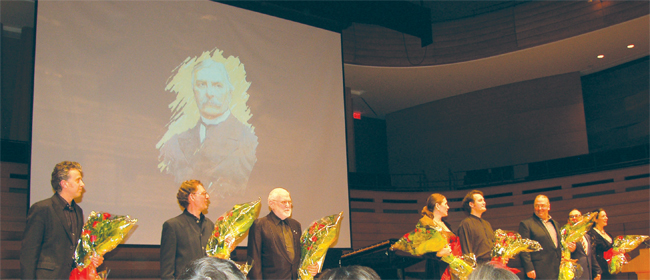

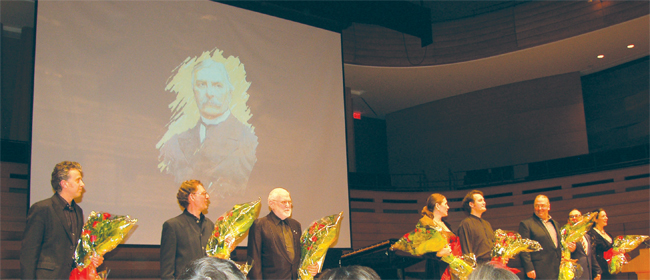

PHOTOS

1 - L. to R.: Roman Borys, Albert Krywolt, Stuart Hamilton,

Krisztina Szabó, Russell Braun, Pavlo Hunka, Roman Hurko and Monica Whicher

after performance of Mykola Lysenko Ukrainian

Art Song, Koerner Hall, Royal Conservatory of Music, Toronto

2 - Pavlo Hunka